Introduction

‘Every work of visual art is a representation of the body’ (Elkins 1999, p.1). Expanding on this statement I will go into discussions on the absent body and the invention of the photograph to which has caused an ocular epistemology. Bodies are everywhere within every day, whether it is the physical body itself or the absent body, we desire to see something familiar to ourselves; many artists have taken this theory further and produced a visual of this concept within their artwork, some consciously done, others subconsciously; This questions the way in which one sees.

The absent body comes in many forms; a trace on the land, a body action documented, or a resemblance of the body within a shape or form. This is simply a change of perspective that allows one to see the body within the everyday. From an architectural build to a cloud, the resemblance of a body can be seen through the naked eye or through the medium of art.

The invention of the photograph has resulted in a huge influence on the perspective of the world and has subsequently changed the way in which others see. The medium of photography has allowed artists to visually capture the real world from their perspective. With the use of photography, it has allowed artists to share their views, thoughts and emotions using the tools that a camera provides. Photography plays a large part on the perspective of the real world, as a photograph allows one to capture a moment in time, in which can be the exact visual replication of the world, even though many aspects such as smell, texture or sound cannot be replicated it can be visually portrayed by specific visuals allowing others to receive more of an understanding on the environment. This type of visual is unable to be replicated through other mediums, such as paint, a painting is not the exact representation of the visual world due to the medium having to be created by hand and with limited colour resulting in the painting to be close, yet inaccurate to the real visual.

Chapter one, ‘Seeing Bodies’ is a discussion on how we see. Throughout this two-part chapter, it covers the invention of the photograph and the effect this medium has on the artistic world; A photograph can change how one sees the world, this is done through the perspective of an artist that questions even the basic principles of the world, to explore the simple act of ‘just looking’, and what it means to see. Photography has opened a large number of new perspectives which has either been discovered or explored through the medium of photography.

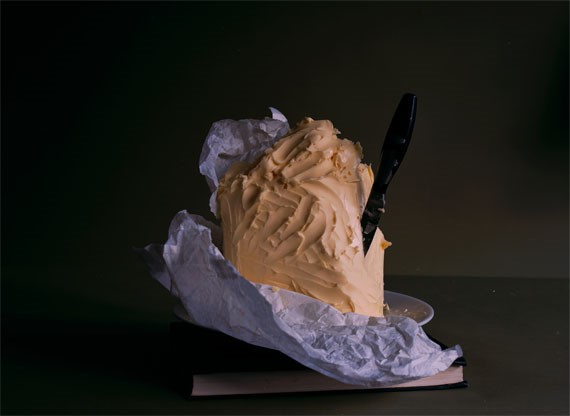

Throughout the second part is a discussion on how one sees the body everywhere; to see the body in an architectural build, nature, shape or form, bodies are everywhere. Introducing the artwork of Pablo Picasso and his cubism to which he plays with the visuals of shapes and forms to create something that is not, using Subjective contour completion to influence ones subconscious to see the body in what the body is not, in order to see something familiar to one’s self. Olivier Richon allows one to see the body in a simple form such as butter, creating a metaphor within the photograph to allow the mound of butter to become a relation to the body, allowing the simplest of objects within the everyday life to be a body.

‘The body as a Tool’ will introduce the discussion on what a body is. Within this discussion is an in-depth dialogue on how the body is used as a tool for the conscious, preconscious and subconscious, this concept will be explored along with theories from Sally O’Reilly and Sigmund Freud. Exploring artists that use their body as a tool within their artwork and artists that have used another’s body as a tool for their artwork. Artists such as Yves Klein, Jackson Pollock and Shigeko Kubota have all used either their own body as a tool or another’s body as the tool, some done consciously, others subconsciously, however, they all support the theory of the body being a tool.

Finally, is the relationship between the body and the land. This relationship explored by the likes of Richard Long shows the way in which one can see the body within the land; this is seen by a trace that is left from the simple action of walking through a field, the photograph shows the body within the land without the physical body being present. However the body can not only be seen in the land but also as the land, to unite the body and the land as one; this is a concept explored in Ana Mendieta’s ‘Silueta series’, this series is a documentation of the land and the body being united as one; as Mendieta states ‘I become an extension of nature and nature becomes an extension of my body’ (Petra Barrera del Rio and John Perreault 1988, P. 10).

Seeing Bodies

The Photograph

Since the invention of photography in the nineteenth century, it has drastically changed the way one sees the world. This invention plays a crucial part in our visual communication, photographs are everywhere in the twenty-first century; ‘The invention of photography is a crucial moment in the development of a modern structure of vision’ (Lalvani 1996, P.2). Subsequently the invention of the camera has allowed photography to create an ocular epistemology. This ocular epistemology has led us to new concepts, theories and an unlimited variation of perspectives. The camera allows one to capture memories and tell stories but has also allowed the artist to share and express their perspective on the world to others.

In recent years photography has become the main source of visual communication. Many artists have used the camera to express their beliefs on their visual concepts of the body, Photography has allowed others to share these concepts and theories this to open new perspectives on how the body is seen; photography has ‘done more than any other medium to shape our notions of the body in modern times’ (Pultz, 1995. P.7).

The camera was designed in 1685 by Johann Zahn, however, the first photograph was taken two centuries away from this. Joseph Nicéphore Niépce born in 1765 in Chalon-sur-Saone, France experienced a comfortable childhood. Niepce developed an interest in science from his brother, Claude, who he began to work with on various experiments and inventions around the years of 1801; The discussion of using light to possibly produce an image began as early as 1793. 1813 was the beginning of the desire for newly invented art within France, this attracted many inventors and artists, including Niépce. During his time in France, Niépce invented the first heliograph, this heliograph is an early photographic process producing a photo engraving on a metal plate coated with asphalt preparation, this was a large step towards the invention of the photograph.

The Heliograph was then later developed by French painter and photographer Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, but It wasn’t until 1838 that Daguerre became comfortable showing examples of his new medium to artists and scientist in hope to find investors. This led to François Arago who invested in the process of the Daguerreotype, which then gave birth to photography as we know it now.

As a result of this invention, photography has become the main source of visual communication. Photographs are everywhere, there is always a need for a photograph. Due to photographs being universal it has allowed it to become diverse. As a result of this diversity, it has allowed many to read photographs and create photographs with visual concepts and theories. Many question what a photograph is, one can photograph the land giving an almost identical 2D visual of the land however it cannot be the land nor feel like the land or smell like the land, giving photography limitation of what one can create, but one can break these limitations within the use of a visual element. The photograph allows many artists to visually communicate their concepts and theories on the visions of the world, to express their emotions and thoughts to others making it a significant medium to many artists. Photography also allows one to see what one may desire but can never witness, the power of photography is astounding, it has given a new way of thinking, taught us and questioned how we use our eyes, to also question what we thought was so simple such as what a body is and how we see bodies; however, bodies are not the only concept that has opened up many questions but it is worth analysing and noting one of the many ocular epistemologies that a photograph has introduced.

Photography is not only an image but also a trace, In comparison to a painting photography allows for a ‘real’ visual, replicating in what an object truly looks like, to capture a moment almost instantaneously, whereas with a painting one can blend moments, creating a false representation of the ‘real’; one is also limited to colours and cannot perfectly replicate the visual of an object that is painted, concluding photography to be the stronger medium in order to capture the ‘real’ ‘a photograph is not only an image, an interpretation of the real; it is also a trace, something directly stencilled off the real’ (Sontag 1977, P. 1).

The invention of the photograph has brought the questions of what is seeing, and, what is not seeing? The act of looking is the simplest form of seeing; However, can we ever ‘just look’? The act of looking is ‘just what the eyes do: they open, they see the world, they close.’ (Elkins 1996, P. 18) but looking is much more than this, there are emotions involved, to just look would eliminate these emotions and action in which an object may bring by being seen.

“When I say, ‘Just looking,’ I mean I am searching, I have my ‘eye out’ for something. Looking is hoping, desiring, never just taking in light, never merely collecting patterns and data. Looking is possessing or the desire to possess – we eat food, we own objects, and we ‘possess’ bodies – and there is no looking without thoughts of using, possessing, repossessing, owning, fixing, appropriating, keeping, remembering and commemorating, cherishing, borrowing and stealing. I cannot look at anything – any object, any person – without the shadow of the thought of possessing that thing. Those appetites don’t just accompany looking they are looking itself”

Elkins 1996, P.22

Seeing causes many effects, one of these effects is to feel a certain emotion through the act of seeing. If one is to be presented in front of a nude photograph, within a public space such as an art gallery, they will begin to feel uncomfortable due to the risk of them being caught staring at the nude body; or another is to be positioned in front of a still life photograph, perhaps a still life of food, one may then begin to feel hungry. Seeing is much more than just opening our eyelids and allowing light in, seeing causes a full-body reaction such as a feeling, an urge or thought depending on the subject one is looking at. ‘one of the most interesting properties of pictures is the way they provoke this stifled dialogue, how they hold out the possibility of disinterested seeing while offering the eyes so much’ (Elkins 1996, P.24).

To see a body is not always to see the physical body within the frame but to see a trace of the body, a metaphor of the body or to relate something other than the body to the body itself, this is act is a desire to see something familiar to one’s self.

Bodies are Everywhere

The body is everywhere, even if the bodies are not actually there; we see bodies wherever we look ‘when I see a form, any form, any shape at all, I am also seeing a body’ (Elkins 1996, P. 125). Within the every day the subconscious will always relate an object to a body, there are many examples of this such as, a house, windows are eyes, doors as mouths and the building as the head. looking up to the sky we are also in search of a body, within the clouds, we search for any shape or form related to a body shape, not necessarily human but animal bodies too; The ancients Greek and their mythology on astronomy, essentially playing dot to dot with the stars in order to visualize their gods within the sky. We that these are not bodies, but we can’t help but relate everyday objects to the body.

“when we are confronted with an unfamiliar object – a blot, a funny smear, a strange configuration of paint, a mirage, a frightening apparition, a wild landscape, a brass microscope, a building made of brick and rock – we seek a body in it; we try to see something like ourselves, a reflection or another, a doppelganger or a twin, or even just part of us – a face, a hand, an eye, even a hair or a scrap of tissue.”

Elkins 1996, P. 129

Many artists such as Pablo Picasso’s and Georges Braque tested this theory within their work of art. This style of art is known as Cubism, Cubism is one of the most influential styles of work in the twentieth century (Rewald 2004). The beginning of 1907 marked the commencement of Cubism, with Picasso’s ‘Demoiselles D’Avigon’. Cubism opened a whole new perspective of visual reality which led to new possibilities within visual art. Cubism was the start for many later abstract styles including constructivism and neo-plasticism.

Pablo Picasso, a Spanish sculpture, etcher, lithographer, ceramist and designer, played a significant role in twentieth-century art, working in various extraordinary styles. Picasso’s Cubist style was influenced by the late artwork of Paul Cezanne in which he painted things from different viewpoints of view and was inspired by African tribal masks; these masks were described as highly stylised, non-naturalistic yet present a human image, a head is the inclusion of eyes, nose, and mouth, these features can be distributed in any way to which it will still form a face.

There are two types of Cubism, both analytical and synthetic. Analytical is the original form of this art form running from 1908 to 1912. Analytical Cubism is made up of intertwining panes and lines that are muted by tones of blacks, greys and ochres. The second style, synthetic, is a later phase of Cubism taking place from 1912 to 1914; this style is characterised by much simpler shapes with brighter colours which often included collaged real elements such as newspapers.

The painting ‘Three Musicians’ (Fig 1) created by Pablo Picasso is a Synthetic Cubist style created in 1921. Measured at over two meters wide and two meters high it is presented in the New York Museum of Modern Art. Picasso’s style of painting is created to give off the appearance of cut paper. Painted are three musicians created from brightly colour abstract shapes in the scene of a boxlike room. On the left is a clarinet player wearing a blue and white suit, in the middle, a guitar player appearing in an orange and yellow diamond-patterned costume and to the right is the singer holding sheets of music, dressed in a black robe; in front of the clarinet player is a table with objects placed on that table, beneath him is a dog with only his belly, legs and tail on show, with a shadow of the dogs head on the wall behind. This entire scene is composed of flat shapes. Between the musicians, it is difficult to determine where one starts and one ends, as all are intertwined together as if they were paper cut-outs.

In many of Picasso’s Cubist work, he introduces subjective contour completion; this is something that Picasso consciously does to influence the viewers subconscious. Named by Psychoneurologists, subjective contour completion is a visual analysis of what cannot be seen; when looking at an object that is not complete the subconscious takes control by completing the object, if part of a body is covered by an object such as a wall, the mind will complete this body by analysing the tone and shape of the body we see, to then complete a false image of what the rest of the ‘missing’ body may look like. We do this as the conscious has a desire for wholeness over dissection, to complete the shape of a body whether it is true or false. Subjective contour completion is subconsciously done in the everyday life of all. ‘our eyes continue to look out at the most diverse kinds of things and bring back echoes of bodies’ (Elkins 1999, P. 1). The continuous search for fulness is not only proven by Psychoneurologists research but also within animal behaviour, as Elkins states ‘when a chimpanzee is shown a chessboard with a black square missing, it will attempt to colour in that square.’ (Elkins 1996, P. 128).

Mound of Butter by Olivier Richon (fig 2) is a contemporary recreation of the oil painting produced by Antoine Vollon in 1975-1985. Since the age of 14 Olivier Richon has used the camera as a tool for documentation. Since 1980 Richon has been engrossed in still life photography. Within his series of still life’s, Richon plays with the viewer’s expectations by equipping his photographs with objects that are overwhelmed with art-historical symbolism.

Mound of Butter is a photograph from Richon’s series, still life. Seen within this photograph is the body, a metaphor of the body. Visually we see, of course, a mound of butter unwrapped from the white packaging that has been placed onto a grey plate, inserted into the butter is a knife, along with finger imprints on the butter. Due to the spotlight lighting used, the butter is noticed first, standing out from the dark background and plate, allowing the butter to be the focus of the photograph. On the butter is smears and imprints from a finger which has left behind the presence of the body; however, this presence of the body is absent, resulting in the signification of the butter to be the absent body. To the right of the photograph is a knife that has been stabbed into the butter, this action is not only a trace of a body action but also a trace of emotion, the knife would have to be inserted with force resulting in the action of anger, frustration or spitefulness. The word stabbed is to thrust a knife or other pointed weapon into ‘someone’ so as to wound or kill; clearly, butter cannot be wounded or killed however due to the butter being the significance of the body this knife is inserted as to wound or perhaps kill the body. These visual elements suggest that the signification of this photograph is a metaphorical documentation of death to the body.

Conclusively this photograph is a visual metaphor of the body. We can not see a body, but we can see a trace and significance of the body, we see the absent body, and there are elements within this photograph which brings us echoes of the body. This is a visual technique using visual elements to replicate what an object is not to which one can capture with the camera, just as Richon has done.

The Body as a Tool

The body is a tool for the conscious. Like a car, the driver wishes to perform an action and uses the car to complete this action; it is the same concept with the body and the conscious, the conscious wishes to perform an action, therefore, will use the body to complete this action. As humans we consistently use the body as a tool, with everyday tasks, from a simple an action such as walking, the conscious knows where it wants to go therefore will tell the body to put one foot in front of the other, then the other foot in front of that resulting in the process of walking. This act of communication between the body and the conscious is controlled by a section of the brain called the cerebral cortex.

The cerebral cortex is a thin layer of the brain that covers the outer portion of the cerebrum, it makes up two-thirds of the brains total mass which lies over a large portion of the brain’s structures. The cerebral cortex is involved in several functions of the body including the determination of intelligence, determining personality, motor function, planning and organization, touch sensation, processing sensory information and language processing. The cerebral cortex is one of the most important aspects of the brain and is the connection that allows total control over the body (Bailey 2019).

The subconscious is complex, Freud used the analogy of an iceberg to describe the three levels of the mind, the conscious, unconscious and the preconscious (Freud 1915). The tip of this ‘iceberg’ is a representation of the conscious mind, this is the mental process of which we are aware of; an example of this would be that one will feel hungry, and as a result of this they will go and make something to eat.

The preconscious contains the thoughts and feelings that one may not be aware of but as a result, may be brought to the conscious. The preconscious existing between the conscious and the subconscious. The thoughts and emotions within the preconscious wait between the conscious and subconscious until these emotions or thoughts ‘succeed in attracting the eye of the conscious’ (Freud 1924, P. 306). The preconscious is like a memory, linking the signifier to the signified; an example would be if one was to see a photograph of themselves as a kid, this would therefore trigger past memories and emotions, these memories would move from the preconscious to the conscious with ease now that these emotions and memories have been recalled.

Within the subconscious, we have no idea what information it holds. Throughout Freud’s experiment in 1915, he found that some events and desires were often too frightening or painful for his patients to acknowledge, Freud believed this information was locked away in the subconscious mind, perhaps through the process of repression. ‘The unconscious mind contains our biologically based instincts for the primitive urges for sex and aggression’ (Freud 1915).

We use our body as a tool for the conscious, preconscious and subconscious; whether this is through communication, actions, emotions or thoughts, these all have effects to the body, they are examples of the conscious using the body to express and perform these expressions or actions. As a result of this, the body is simply a tool for the conscious, preconscious and subconscious and this is a concept that many artists have taken within their artwork.

There are many artists that use this tool within the use of their work. As well as using the self’s body, one can also use another’s body as a tool. An artist who has taken this perception further is an artist named Yves Klein. Klein was a French-born artist in the twentieth century, a leading member of the French artistic movement of Nouveau realisme founded in 1960 by art critic Pierre Restany.

Klein not only uses his body as a tool but also used the female body as his tool within his work. Take his work ‘Anthropometry of the Blue Period’ 1960 (fig 3) as an example of using another’s body as a tool. What Klein did to create this work was to tell the female collaborators to cover their torso and thighs with ‘international Klein blue’, he then imprinted the female body onto a blank canvas. During this performance, Klein would also have musicians playing Klein’s Monotone Symphony (a single note played for twenty minutes, followed by twenty minutes of silence). This process is using the female body as a tool, the scenario that Klein created has replaced the paintbrush as the female body resulting in the female becoming the brush. The female and her body had very minimal control over the creation of this work as Klein would give precise instructions as to how he wanted the paintings created. This allowed Klein to express his emotions and concepts with the use of another’s body. By having control of this body Klein would leave the body present yet absent within the painting.

Klein’s interest in Anthropometry (the scientific study of the measurements and proportions of the human body) is what drove him to create a series of anthropometric paintings using his own colour international Klein blue. By using another’s body to create his work allowed him to distance himself from the art.

“Having had rejected brushes as too excessively psychological already earlier, I painted with rollers, in order to remain anonymous and at a distance between the canvas and myself during the execution, at least intellectually… I very quickly perceived that it was the block of the human body, which is to say, the trunk and a part of the thighs that fascinated me. The hands, the arms, the head, the legs were of no importance. Only the body is alive, all-powerful, and it does not think. The head, the arms, the hands are intellectual articulations around the flesh, which is the body!”

Y. Klein 1960

Klein did understandably gain some criticism from feminists and many female artists for ‘objectifying’ women. This is a very valid opinion as Klein did use the female body as a tool, these female models were known as ‘living brushes’ at the time but most have taken the effort to deny these sexist theories by stating that Klein treated women respectfully during the performance process and would treat them as collaborators.

Klein took performance and painting into a new perspective with this technique. By directing the brush rather than controlling the brush he had given his art a whole new perspective; giving a new way of experiencing and expressing himself with paint which is what Klein was always in search to do. Elena Palumbo-Mosca (a female collaborator) stated in an interview with Tate, 2013,

“I think it’s Yves’s work, he was the mind behind it, and I was able to understand and to turn his ideas into something tangible. I just look at what I was doing, and I think it was interesting, and I think I was quite lucky to participate in this experience.”

Palumbo-Mosca, 2013

Many reviewed the question on whether this was Klein’s work or not due to the fact of him only directing and not physically contributing; even though Klein is not physically contributing to his work he is expressing his visions and his emotions by directing his contributor on what to do and where to do it, this is the same concept we have with the conscious and the body, the conscious expresses and directs the body to do what the conscious wants it to. Klein has simply replaced the tool from being his body to another’s body.

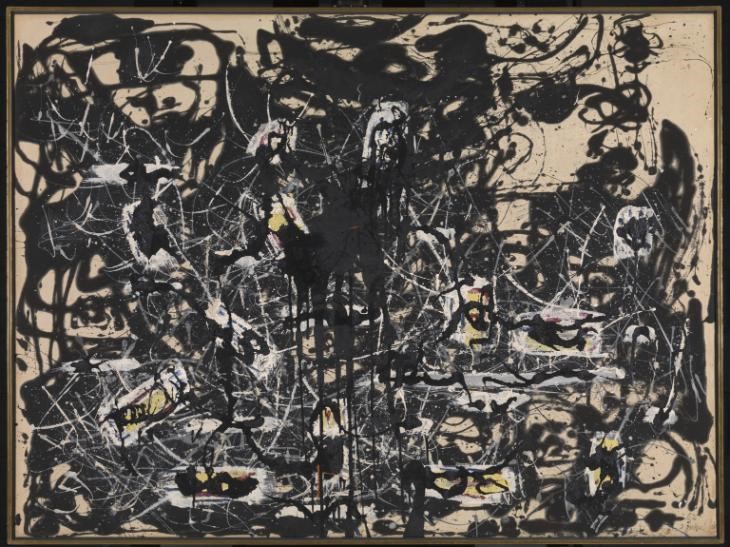

The body is not only a tool for movement but for emotion too. From consciously feeling an emotion we portray this emotion using the body; this can include body language, facial expressions and our tone of voice. As a viewer, we can mostly understand these emotions and feelings that a body is portraying by reading their body language or engaging in a conversation with this person. These emotions can also be portrayed within an art form, ‘explicit paintings presenting a study of the body as an instrument for experiencing and expressing pleasure, pain and desire’ (O’Reilly 2009, P.29). O’Reilly clarifies the body’s way of expressing emotion, from the use of art one can portray their thoughts and feelings using colour, composition and action. This form of art is called abstract expressionism, developed by American painters such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning in the 1940s and 1950s. The intention of this art form is to make art that is abstract but with an expressive or emotional effect. Many artists of abstract expressionism were inspired by surrealistic art that should come from the unconscious mind.

There are two groups of this form, one being action painters. Action painters such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning worked in a spontaneous improvisational manner, who often used large brushes in order create sweeping gestures onto the canvas rather than delicately applying it. The term American Action Painter was composed by Harold Rosenberg in his article ‘The American Action Painters’ published in ARTnews on December 1952. Pollock famously danced around his canvas pouring paint from the can or trailing it from the brush or a stick; by doing this he is documenting his body actions through the use of paint, again using the body as a tool for expressing and directly placing their inner desire onto the canvas, this has brought emotion to the painting through the actions of the body.

Jackson Pollock, a respected action painter within the abstract expression art group is an American artist from the twentieth century. Pollocks work does tend to include action and movement within his paintings, this may include leaning, stretching, splattering, dancing, smearing, drooling, stomping and more. Pollock, therefore, uses his body as a brush, by letting the paint drip off his body or let the paint smear off his body onto a canvas from the action that he is performing. Pollock documented his body’s movement and actions within his paintings.

Pollocks work ‘Yellow Islands, 1952’ is an excellent representation of abstract expressionism. Yellow Islands is a large oil painting on a rectangular, horizontal oriented canvas. The abstract patterns and composition were created by pouring layers of paint onto the beige canvas; the colour black and white being used as the thinner first layer of paint creating thin lines throughout the painting; then a thick layer of black paint was poured over the white and black paint creating a glossy finish creating a sense of texture, depth and movement to the piece of art; after the black and white paint was dry Pollock then went onto include crimson yellow onto the canvas in small patches using a brush. Within 1951 and 1954 Pollock moved away from the technique of dripping the paint and moved onto the less restricting technique of pouring as he does in Yellow Islands, this series became known as Pollock’s ‘black pouring’s’; a technique that art critic Clement Greenberg described as ‘a turn but not a sharp change of direction; there is a kind of relaxation, but the outcome is a newer and loftier triumph’ (Greenberg, C. 1952, P.102). Using the technique of pouring, Pollock would apply the paint from above moving his body in a circular motion around the canvas to which he later names ‘the arena’; Pollock then applies further layers of paint and while still, wet Pollock would lift the canvas, allowing it to run. This added texture and movement to the paintings. ‘Yellow Islands’ named by art historian Michael Fried as ‘one of the last if not the very last, in which white skeins of paint have been laid down over black underpainting, along with seven or eight small patches of yellow and a few touches of red.’ (Fried, M. 2015. P.87).

From Pollock subconsciously creating ‘Yellow Islands,’ it has allowed his subconscious to take complete control. ‘When I am painting, I am not much aware of what is taking place’ Pollock, 1947 (Art Uk). The act of muting the conscious mind over the making process is called automatism. Automatism is commonly associated with physiology, it describes bodily movements that are not consciously controlled, such as breathing. Sigmund Freud used this method to explore the unconscious mind of his patients. Pollock, therefore, uses automatism in his paintings such as ‘Yellow Islands’.

By removing the conscious from the art this allows the subconscious to use the body as a tool, a tool for expressing emotion, movement and for the viewer to see deep into the subconscious mind of the artist. In ‘Yellow Islands’ the predominant colour is black, black is associated with the feeling of sadness, depression and loss; this colour black has also been created by the movement of pouring, something that is difficult to keep control of, a lot messier than using something like a brush, therefore the use of black would represent the lost control of depression or a negative emotion within the mind, most likely pollock would have been feeling dismal and abandoned or undisciplined; black is also an absorbing colour, absorbing light and in this case absorbing the emotions around it. Between the pours of black, there is yellow, the emotion related to yellow is happy, cheerful and positive; of course, this colour is emotionally the opposite to the colour black. It is also worth pointing out that the colour yellow is painted from a brush, something that Pollock has much more control over resulting in a more stable feeling of positive emotion. Also included in the painting is the colour white, most of the white is surrounding yellow paint; white expressing clarity and total reflection would tell the viewer that these positive feelings are supported by a clear reflection, perhaps a reflection on himself, his own actions. Looking at the canvas as Pollock’s subconscious we see a controlled positive emotion supported by clear and proud reflections of himself but being absorbed by the negativity that is out of his control; by looking at this painting Pollock would not have been in such a healthy mental state. However, there is a glance of positivity supported by a reflection on his own actions deep within his mind. This shows how the subconscious can use the body as a tool to express an emotion that even the artist may not perceive.

The second group of abstract expressionists were interested in religion and myths. The group included artists such as Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman and Clyfford Still who created simple compositions along with large areas of colour to produce a thoughtful and reflective response for the viewer. The development of this 1960’s group then went on to become known as colour field painting, introducing the likes of Helen Frankenthaler, Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland and many more. Colour field painting now differs from abstract expressionism by removing the emotional, mythical and religious content on the past movement.

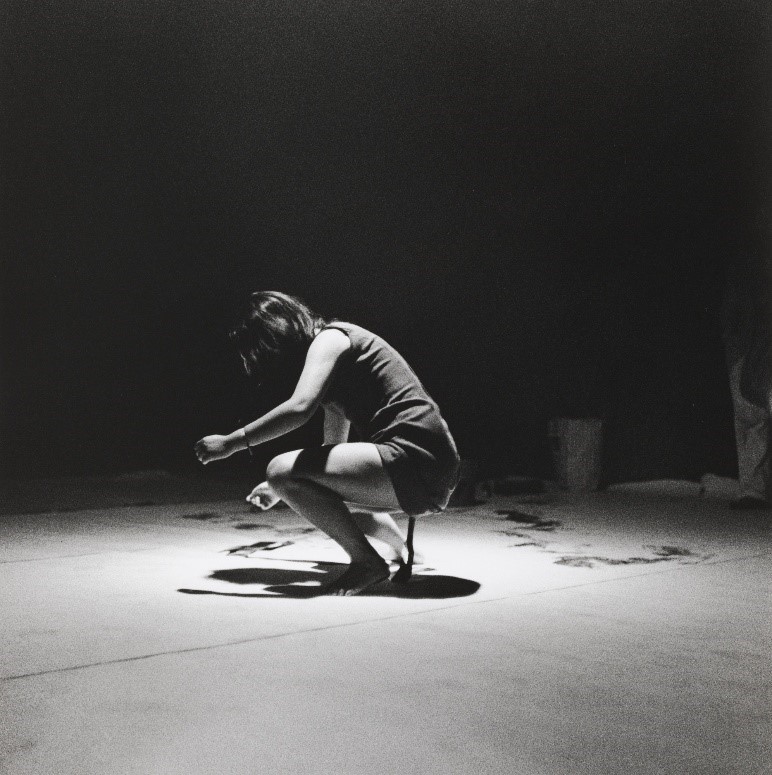

In 1960 another abstract expressionist came into the male-dominated group. This artist was Shigeko Kubota. Kubota was a female Japanese performance artist who became a key member of the Japanese Avant-Garde, a participant in the New York Fluxus events in the 1960s and then progressing into a pioneering practitioner of video art at the beginning of the 1970s. The Japanese group Avant-Garde were a group of artists who pushed the boundaries of art, including music, performance and movement into their work. The Avant-Garde turned the war-torn nation of Tokyo into an international centre for art, culture and commerce; this then led to the individual focus on creatives in various art forms such as painting, sculpture, photography, drawing, graphic design and video. The purpose of this group was to question the authority of the post-war Japanese government and what the government viewed as the focus on economic growth at the expense of the wellbeing of individual citizens.

Many critics in Japan were particularly biased towards female artists and as a result of this Kubota left to pursue her career in New York where she believed she would find many better career opportunities. Kubota’s most famous work was her Vagina Painting in 1965, which she presented as part of the continuous Fluxfest in New York on 4th July. In this performance Kubota attached the handle of the paintbrush to her underwear to which she then squatted over a bucket of red paint and made her way across a large sheet of paper laid on the floor, creating menstrual-like smears.

The audience was present during the performance of Kubota’s work causing an interaction between the artist and the audience. The woman’s body is no longer passive, (as many Japanese art critics believed in this time frame) but creative and active. The position of the brush and the colour is chosen leads to believe that the artwork included the concept of femininity and their rights, due to the introduction of the contraceptive pill in America. As a result, Kubota is documenting her actions by waddling and crouching around her sheet of paper leaving behind documentation of the body’s actions; like Jackson Pollock’s ‘drip paintings’ Kubota is recreating this drip technique to emphasize the process of the female body. Not only is Kubota documenting her actions but also documenting the actions and process of the female body. By using the colour red, the paint signifies the menstrual blood, this is something that only the female body produces and is an act that takes place every month; Kubota is not only documenting the body’s actions but also the actions and process of the female body itself, signifying that the body is also a tool for reproduction.

The Body and The Land

The body and the land have a fascinating relationship. The body can be seen within the land and the land can be seen within the body; The land can be the body and the body can be the land. The use of photography plays an important role within this concept as it allows many to play with the visual aspect of looking even though we are never just looking.

The body leaving traces through the land, the use of the body on the land can impact the land itself. One of these effects is the desire line. A desire line is a path that pedestrians or vehicles informally take rather than taking the set route, this can be seen in many places such as patches of grass or in the snow. The body performing the simple act of walking through the delicate land leaves traces of itself. Artists have used the medium of photography to share their experienced relationship between the body and the land, exploring the means of the absent body, the traces and affects the body has on the land.

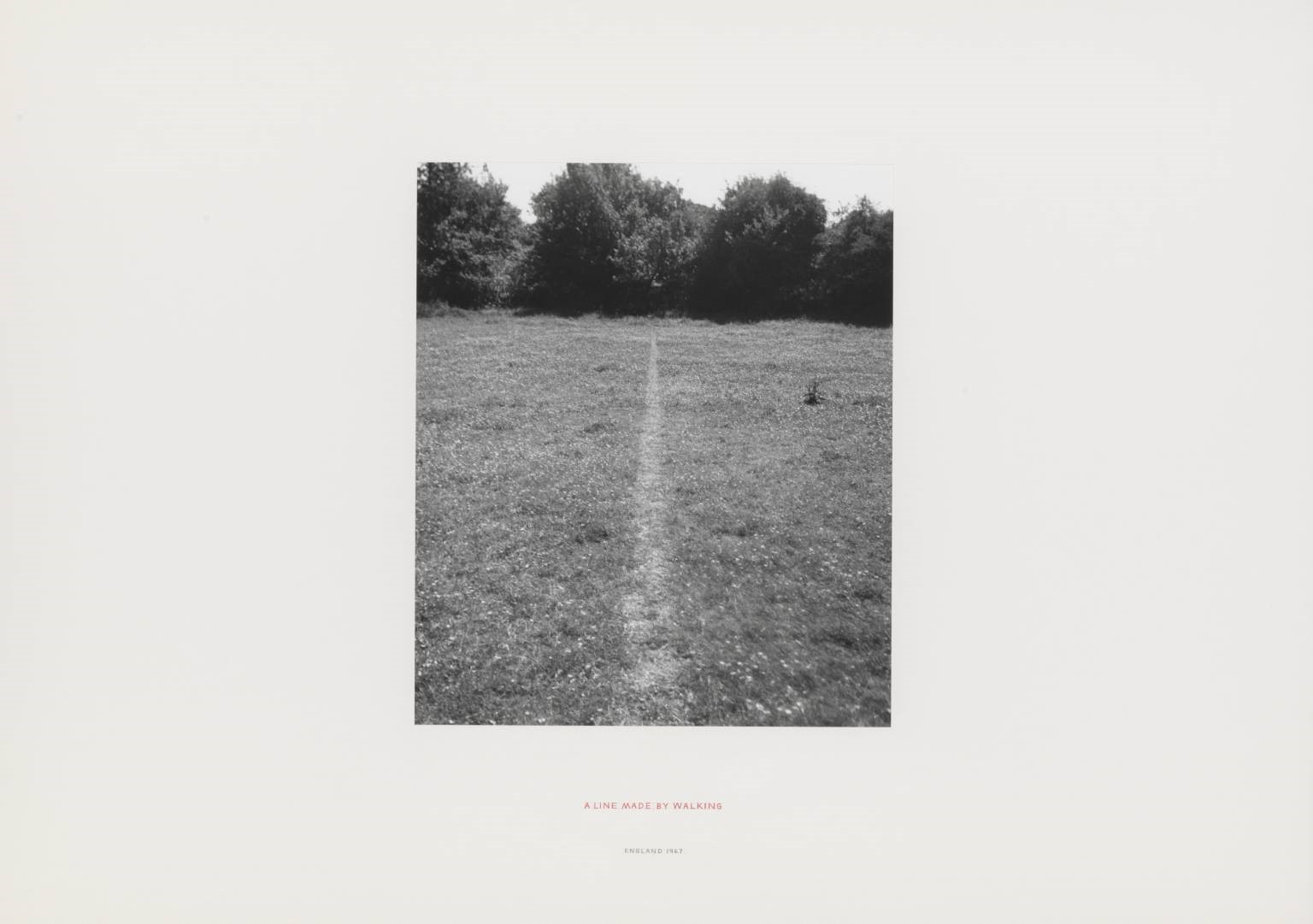

Richard Long is a contemporary artist born in 1942 in Bristol, England and is still based within Bristol. Long is a Sculptor and practitioner of land art, Long has created many art forms from the use of walking in landscapes, this documented action of walking shows the absent body within his work, there is no physical body in the frame however there are traces and marking left within the landscape showing the viewer the absent body. Long’s most famous art is his ‘A Line Made by Walking’ (fig 6). This black and white photograph shows a straight line of trampled grass leading towards trees or tall bushes in the distance.

The photograph documents an action of the body, the action of walking. The desire line was created by Long himself, he would pace up and down the grass field until the desire line was made clear to the eye, once this was done Long would, of course, photograph his absent body within the land. While still a student at St Martin’s School of Art, London in June 1967, Long took a train from Waterloo station heading south-east unknown of his destination. Coming across this field just twenty miles out Long then decided to create ‘A Line Made by Walking’.

“Nature has always been recorded by artists, from prehistoric cave painting to twentieth-century landscape photography. I too wanted to make nature the subject of my work but in new ways. I started working outside using natural materials like grass and water, and this evolved into the idea of making a sculpture by walking … My first work made by walking, in 1967, was a straight line in a grass field, which was also my own path, going ‘nowhere’. In the subsequent early map works, recording very simple but precise walks on Exmoor and Dartmoor, my intention was to make new art which was also a new way of walking: walking as art.”

Tufnell 2007, P.39

‘A Line Made by Walking’ is a documentation of an action that a body takes, in this case, it is the action of walking. The photograph is also including the landscape, the body along with the use of performance art (as he performed the action that is visible within the photograph). The inclusion of many subjects has stretched the means of photography and how we see photographs and bodies. The photograph by Richard Long allows us to see the body within the land.

Other artists have also explored the concept of the body and the land with different approaches to the subject. Some artists wish to unite themselves with the land and become one with the land, to become an extension of nature. Artists such as Ana Mendieta use the land and their body in a way that connects the two, allowing both the body and the land to become one.

Ana Mendieta was a Cuban American artist in the twentieth century. Mendieta was known to explore the mediums of photography, performance, videography and sculptor. Within these mediums, Mendieta would explore the relationship between the female body and nature. Exploring the relationship between the body and the land Mendieta would Work with photographs and video footage of her own body, camouflaged within the natural environment.

Throughout 1948 to 1985 Mendieta produced one of her most renowned series of work, this series was named the ‘Silueta Series’. Exhibited as Photographs the ‘Silueta Series’ is a spiritual connection between nature and the body, Mendieta would carve and shape her female figure into the earth. Mendieta would shape her body in different positions depending on the natural element she would be replicating; these positions would include her arms overhead to replicate the amalgamation of the earth and the sky, the body floating in the water which would symbolise the minimal space between land and sea, or with her arms raised and legs together to signify a wandering soul. The composed body traces all have connections and representations of the land, using the body shape and position to symbolise each element of the earth, combining the body to the land.

The colour photograph (Fig 7) taken in the ruins of the ‘Labyrinth’ in the Palace of Six Patios at Yagul, is an archaeological site in the valley of Oaxaca, Mexico. In the foreground of the photograph is the low stone ruins and to the floor of these ruins is a Silhouette of Mendieta’s body; beyond the stone ruins are natural green mountains, reaching up to the cloud-covered sky. The ‘Untitled’ photograph from the ‘Silueta Series’ is only the second of over one hundred photographs created in Mexico and Iowa but the first one using the outline of her body rather than the body itself. The positioning of the body within this photograph is a signification of the wandering soul, her arms raised above her head (in reference to the Minoan snake goddess) and legs together suggest this. To create this Silhouette Mendieta lay on the land, positioning herself to the relevant position of the body which then allowed Hans Breder (Mendieta’s Lover and teacher) to create an outline of her body. Once this outline was created Mendieta scooped out the earth to make a body shaped indent within the floor, Mendieta then used the blood that she gained from a butcher in the market city of Oaxaca to pour into the earth which created a blood-filled silhouette of Mendieta’s Body.

Mendieta explained the concept of her ‘Silueta Series’:

“I have been carrying out a dialogue between the landscape and the female body (based on my own silhouette). I believe this has been a direct result of my having been torn from my homeland (Cuba) during my adolescence. I am overwhelmed by the feeling of having been cast from the womb (nature). My art is the way I re-establish the bonds that unite me to the universe. It is a return to the maternal source. Through my earth/body sculptures, I become one with the earth … I become an extension of nature and nature becomes an extension of my body. This obsessive act of reasserting my ties with the earth is really the reactivation of primeval beliefs … [in] an omnipresent female force, the after-image of being encompassed within the womb.”

Petra Barrera del Rio and John Perreault, 1988, p. 10

Using 35mm colour film Mendieta has captured a specific moment in which she has created. By using photography (taken by Breder), she has allowed herself to document and capture the body and the land as one. Using Photography as the tool to express and share her concept and mindset with others, through other artistic mediums such as painting it is much more difficult to capture a specific moment and capture both the land and the body in the exact visual replication. The use of the signified body positions and use of objects/materials along with the involvement of the land has therefore allowed and united both the both and the land, the evidence of this uniting is proved through the medium of photography helping others to understand and analyse Mendieta’s relationship between the body and the land.

Conclusion

The invention of the photograph has given artists the tool to explore other perspectives and concepts of the world. With photography being the main source of visual communication, photographs are everywhere, we have become familiar with photographs. From exploring these perspectives and concepts others have begun to share their own perspectives introducing us to many new topics and theories such as the absent body. But what is a photograph? We can supposedly replicate the ‘real’ however we can not capture the smell, texture or sound of objects or environments, but one can use visual elements to replicate these senses. Photography has brought up questions to the most ‘simplest’ of topics, creating an ocular epistemology. A simple topic such as seeing has been explored by photographers and artists to which they have questioned, what is seeing? The simplest form of seeing is ‘just looking’, however, we are never ‘just looking’, to just look takes away the reactions such as emotions, urges and actions that would be caused by seeing, an example of this reaction would be to see food, whereas a result of seeing food one may begin to feel hungry; seeing is just the beginning of what we do or feel.

To see a body is not just to see the physical element of the body. The body can be absent, as a trace, metaphor, shape or form, we see echoes of bodies within the everyday. Bodies are everywhere, including this text, this text is a representation of a body, even if we take away all the photographs and all words relating to a body, the text still has a header, a footer, a body and other texts may also have shoulder notes. Photography has allowed us to capture and documents the absent body within the real, such as traces on the land, one can instantaneously photograph this trace with a camera allowing one to photograph this absent body, turning something temporary into something permanent. One’s subconscious will always relate an object to the body, we desire to see fullness over dissection. Subjective contour completion is something that is subconsciously done by all, if we can not see the full-body, if a leg or arm is hidden by a wall or such we will subsequently complete this body ourselves by analysing the body in which we can see, creating a false image of that arm or leg.

The body is a tool for the conscious. Looking into experiments from Sigmund Freud, it shows that the body is a tool, the subconscious, preconscious and the conscious is the driver of this tool. Using the cerebral cortex, the conscious wishes to perform an action or an emotion, the conscious then tells the body what it wants to do, whether this is a change of facial expression or even an urge to perform an action which can be consciously done or even subconsciously done. Artists have used this tool within their artwork, such as Yves Klein. Rather Klein using his own body as a tool, he uses another body as the tool, by directing the co-collaborators body he is expressing his concepts and actions through the means of another body, taking control of this co-collaborator and using her body as a tool for himself. Other artists named action painters such as Jackson Pollock allowed his subconscious to take control of his body; as a result of this, the subconscious has expressed emotions using body actions to which Pollock may not have fully understood himself, using colours and actions through his paintings, give us an understanding of what Pollock’s subconscious may be thinking or feeling, to which this has been expressed through paint. Shigeko Kubota also used her body to express her conscious thoughts on the reproductive system and the introduction of the contraceptive pill in America. Kubota used her body as a tool to express her emotions and actions of which the female body produces in order to spread awareness of what is being introduced.

The body and the land have an interesting relationship. Through the artwork of Richard Long, we see the body within the land, as Long has photographed the trace of his body. Longs photograph was taken almost instantaneously allowing him to capture the absent body walking through the field. The body can not only be seen within the land but also as the land, Mendieta’s ‘Silueta Series’ unites the body and the land as one. The land becomes an extension of her body and the body becomes an extension of the land. Photography plays a large part in this concept as it is able to capture moments within the real, a moment where the body is present with the land; as within Long’s photograph the trace of this body would have disappeared within a few days due to the grass growing out again, and also the silhouette from Mendieta’s ‘Silueta Series’ will not last forever; photography has allowed one to photograph these temporary moments and turn them into permanent moments through the means of a photograph, capturing a trace of the temporary land.

Bibliography

Art UK. Yellow Islands. [online] Artuk.org. Available at:https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/yellow-islands-117781 [Accessed 19 Dec. 2019].

Bailey, R. (2020). What Does the Brain’s Cerebral Cortex Do? [online] ThoughtCo. Available at:https://www.thoughtco.com/anatomy-of-the-brain-cerebral-cortex-373217 [Accessed 27 Dec 2019].

Elkins, J. (1996). The object stares back. San Diego, Calif. Harcourt.Elkins, J. (1999). Pictures of the Body: Pain and metamorphosis. Stanford University Press.

Freud, S. (1915). The Unconscious. SE, 14: 159 – 204.

Freud, S. (1924) A general introduction to psychoanalysis, trans. Joan Riviere.

Fried, M., Delahunty, G. AND Applin, J. (2015) Blind Spots: Jackson Pollock. Tate Publishing & Enterprises.

Greenberg, C. (1952). Art Chronicle: Feeling is All. Partisan Review 19 (January – February).

Klein, Y. (1960). Excerpt from << Truth become Reality >>, Overcoming the problematics of Art – The Writings of Yves Klein, Sprint Publications, 2007.

Lalvani, S. (1996). Photography., Vision and the production of modern bodies. Albany: State Univ. of New York Press.

O’Reilly, S. (2009). The body in contemporary art, New York, Thames & Hudson.

Palumbo-Mosca, E. (2013). Yves Klein, Anthropometries. [online] Tate. Available at:https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/yves-klein-1418/yves-klein-anthropometries [Accessed 29 Nov 2019].

Perreault, J., Barreras del, R. (1988) Ana Mendieta: A retrospective, The New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York.

Pultz, J. (1995). Photography and the Body. Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Rewald, S. (2004). Cubism. [online] metmuseum.org. Available at:https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/cube/hd_cube.htm [Accessed 28 Jan 2020].

Rosenberg, H. (1952). The American action painters. ARTnews.

Sontag, S. (1977). Photography Unlimited. The New York Review.

Tufnell, B. (2007). Richard Long: Selected Statements & Interviews, London.

Illustrations List

Figure 1 – Pablo Picasso, 1921. Three Musicians, Museum of Modern Art. New York.

Figure 2 – Olivier Richon, 2016. Mound of Butter.

Figure 3 – Yves Klein, 1960. Barbara (ANT 113), post-war and contemporary art. New York.

Figure 4 – Jackson Pollock, 1952. Yellow Islands, Tate. London.

Figure 5 – Shigeko Kubota, 1965. Vagina painting. Performed during Perpetual Fluxfest, Cinematheque. New York.

Figure 6 – Richard Long, 1967. A Line Made by Walking, Tate. Liverpool.

Figure 7, Ana Mendieta, 1974. Untitled (Silueta Series, México), Tate. New York.